Towards an Implementation of Structured Cooperation

Table of Contents

In the previous article, I gave you a whirlwind tour of some of the features of Scoop, a POC implementation of something I’m calling structured cooperation. I showed you how making the components of a distributed system obey a single, simple rule made the resulting system easier to reason about, behave predictably in the presence of failures, and also allowed us to recover features we know from “regular” programming, such as distributed exceptions and resource handling. However, I didn’t go into too much detail about how exactly Scoop implements structured cooperation, and also glossed over some very fundamental issues that arise in this context—most especially the topic of “how does Scoop figure out which handlers it should be waiting for in the first place.” This is what I’d like to discuss in this article.

To give you an idea about the level of abstraction this article is situated at—if, in the previous article, I had

talked about “what would we get if computers could communicate statelessly across the internet,” then this article would

be about the HTTP protocol. In that metaphor, Scoop is a POC webserver, and the technical details of how that web

server is implemented is an equally interesting subject—in the case of the actual Scoop, it involves an implementation

of distributed coroutines on top of Postgres. However, that’s not something that we’ll be discussing here. For that,

I’ll direct you to the README in the repository and the heavily commented

codebase itself—I wrote it with the assumption that it was going to be read, and did my best to make it accessible and

understandable.

I should also note that I often use the terms “saga” and “(message) handler” interchangeably, because in Scoop, they are—all message handlers are sagas, and all sagas are message handlers. Naturally, that is not the case outside of Scoop.

Implementing Structured Cooperation #

Let’s restate the fundamental rule of structured cooperation:

A message handler (= saga) does not continue with the next step until all handlers of all messages emitted during the current step have finished executing.

To implement that, you need two things:

- Keep track of which messages were emitted from which step of which saga

- Be able to figure out if a handler has finished or not

Keeping track of where messages came from #

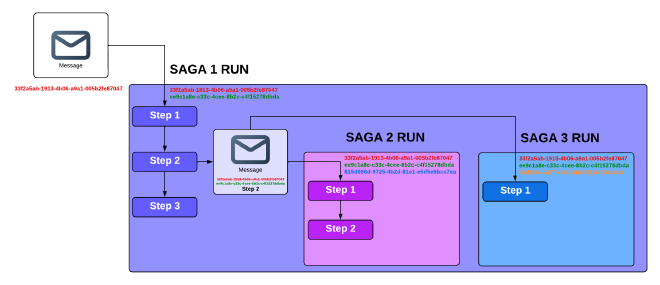

Scoop does this by associating a list of unique UUIDs, called a cooperation lineage, to each emitted message, and to each saga run. Any time a message gets emitted by some place, and a saga picks it up and starts running, that entire run (i.e., all the steps involved in that execution, including any rollbacks) is assigned a UUID (called a cooperation ID), which is appended to the cooperation lineage.

When a message is emitted from within a saga run, it is tagged by the cooperation lineage of the run, the name of the step, and any sagas that run as a result of this message build their own cooperation lineage by appending their unique cooperation ID to the cooperation lineage of the message, and so on. Any top-level message (i.e., one emitted outside a saga, or on the global scope, which is the same thing), has a cooperation lineage of length one.

Doing it like this has the effect of structuring the saga runs into a parent-child hierarchy, and allows us to refer to

useful parts of this hierarchy. A specific run of a saga can be queried for as WHERE cooperation_lineage = <some UUIDs>. A run of a saga and its entire sub-hierarchy, i.e., any sagas that were triggered as the result of a message,

directly or indirectly, can be queried for as cooperation_lineage is prefixed by <some UUIDs>1.

This “subtree” is conceptually (but not literally) enclosed by something called a CooperationScope, which intuitively

corresponds to the three large colored rectangles on the picture above. You will find an object called

CooperationScope in the code, and is meant to represent something that spans the entire saga run, and all its

children. If you’re familiar with structured concurrency, this is, to an extent, the conceptual counterpart of something

found in almost all implementations—in Kotlin coroutines, it’s the

CoroutineScope,

in Trio, it’s the Nursery , in Java, it’s

the

StructuredTaskScope,

in Swift, it’s the TaskGroup. It’s also the type of that

scope parameter you’ve been seeing in all the code examples, and the picture above lends interpretation to “launching

a message on a scope.”

If the stuff about CooperationScope is too confusing or abstract for you, don’t worry about it; you don’t need to

understand all that to understand structured cooperation. It’s more about connecting it to other existing concepts some

people might be familiar with.

Keeping track of execution state #

Anytime something interesting happens, e.g., a handler sees a message published on the topic it’s subscribed to, or

finishes executing a step, or a rollback gets triggered, or the entire saga run finishes, etc., Scoop makes a note of

that fact. It does so by writing an entry into a special table, called message_events, that stores, well, events

related to message handling.

That table serves two purposes:

- To determine if a given saga is ready to move on to the next step

- To build the state necessary to actually run that step (we need to know things like what step we should execute next, if any children failed during the last one, if a rollback is already in progress, etc.)

I think it might be easier to show you what it looks like before I dive any deeper. Here is some (simplified) code that defines two sagas, and publishes a message:

messageQueue.subscribe(

"root-topic",

saga("root-handler") {

step { scope, message ->

scope.launch("child-topic", JsonObject())

}

step { scope, message -> }

},

)

messageQueue.subscribe(

"child-topic",

saga("child-handler") {

step { scope, message -> }

step { scope, message -> }

},

)

messageQueue.launch(rootTopic, JsonObject())

And here’s what message_events would look like after this finishes running, ordered by time:

| message_id | type | coroutine_name | coroutine_identifier | step | cooperation_lineage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b796 | EMITTED | null | null | null | {56b9} |

| b796 | SEEN | root-handler | 5191 | null | {56b9,5310} |

| 4501 | EMITTED | root-handler | 5191 | 0 | {56b9,5310} |

| b796 | SUSPENDED | root-handler | 5191 | 0 | {56b9,5310} |

| 4501 | SEEN | child-handler | 62b8 | null | {56b9,5310,6817} |

| 4501 | SUSPENDED | child-handler | 62b8 | 0 | {56b9,5310,6817} |

| 4501 | SUSPENDED | child-handler | 62b8 | 1 | {56b9,5310,6817} |

| 4501 | COMMITTED | child-handler | 62b8 | 1 | {56b9,5310,6817} |

| b796 | SUSPENDED | root-handler | 5191 | 1 | {56b9,5310} |

| b796 | COMMITTED | root-handler | 5191 | 1 | {56b9,5310} |

I truncated all UUIDs to the last four characters to save visual space, and I’m also leaving out a few columns for the

same reason: id, the primary key of the row, created_at, which contains the timestamp the row was inserted,

exception, which only comes into play when dealing with rollbacks, and context, which is used to share data across

steps, or even across different parts of the cooperation hierarchy. We’ll talk more about the latter two later on. In

this example, both columns are null everywhere.

| Column | Explanation |

|---|---|

| message_id | The id of the associated message in the messages table |

| type | The identifier of the type of event that occurred. More on this bellow |

| coroutine_name | The name of the handler/saga, if present |

| coroutine_identifier | The identifier of the handler/saga (for situations where the service is scaled horizontally) |

| step | The step name (or its ordinal, if not specified), if applicable |

| cooperation_lineage | Explained above |

With this setup, adhering to the rule of structured concurrency essentially boils down to building a (moderately

complicated)

query

that checks if a saga is ready to proceed or not. In Scoop, that amounts to asking “for all messages emitted in the

previous step, does every SEEN have a corresponding COMMITTED” (plus the equivalent for rollbacks, which we’ll get

to).

In other words, when you strip it down, Scoop is essentially this:

- Provide a way to publish messages to topics

- Provide a way to associate an object (= saga/handler) containing a list of functions (= steps) to a topic

- When that association is created, launch a periodic process that, on each “tick”:

- Checks if an as-yet-unseen message was emitted to that topic. If so, it launches a new saga run (amounts to writing

the

SEENrecord above). Also performs something similar for rollbacks. - Runs the query mentioned above and checks if any existing run is ready to continue. If so, it uses the contents of

message_eventsto pick the correct function (step) to run, and invokes it. When it finishes, it writes the appropriate row tomessage_events, depending on the result2. This also makes it non-blocking by design, i.e., there aren’t any processes waiting around until something else finishes.

- Checks if an as-yet-unseen message was emitted to that topic. If so, it launches a new saga run (amounts to writing

the

And that’s pretty much all there is to it.

With one exception.

EventLoopStrategy #

This entire time, we’ve been skirting a fundamental issue, one that profoundly influences the properties of the system you end up building with Scoop.

The rule of structured cooperation is “don’t continue until all handlers have finished executing.” So how do you know

which handlers you should be waiting for in the first place? When you think about it, it’s not obvious what the correct

answer is. For example, a naive approach could be, e.g., “After a message emission, just wait for X amount of time, after

which all registered handlers will surely have seen the new message and written their SEEN event. Then, wait until

those SEEN’s are terminated.”

But what if a network partition happens, and some handler is not available for a period of time longer than it takes all

the others to complete? What if you just deployed a new service that happens to be listening to that message? What

happens if the SEEN was written, so you know you should be waiting for it, and then a network partition occurs? Or

you take the service offline deliberately?

All of these, and more, are questions you need to ask yourself, and there is no one correct answer—the answer is “it depends.” Scoop recognizes this, provides an API that’s deliberately designed around the fact that you need to figure this out, and forces you to make an explicit decision.

It turns out that this is a specific instance of a more general question: under what conditions is a saga ready to be resumed? Naturally, the way we’ve been answering this question this entire time is “when the rule of structured concurrency is obeyed,” but that’s not the only useful answer.

Here’s another one: when a certain amount of time has elapsed. And boom! You just got sleep() for free. And when you

have sleep(), you also have task scheduling. Just like that.

An associated question you can ask is, under what conditions should you give up on a saga? Here are some useful answers:

- when a deadline has passed,

- when a cancellation has been requested.

Again, you get powerful and well-established features, but you don’t get them as primitives that need to be built in, but rather as things that are built on something even more fundamental. If Scoop didn’t implement timeouts or cancellations, you could just as easily do it yourself.

The API in question is called an EventLoopStrategy, which is an interface exposing five methods: resumeHappyPath,

giveUpOnHappyPath, resumeRollbackPath, giveUpOnRollbackPath, and start. We’ve introduced the former two, and the

following two are the equivalent for rollbacks. The giveUp variants are checked by Scoop automatically on the

“boundaries” of a step, i.e., before a step starts executing and after it stops. You can also check it on demand from a

step by calling scope.giveUpIfNecessary() inside a step, which will throw the appropriate exception if

necessary—Scoop is cooperative. Finally, start is there to

allow you to customize under which conditions you want to react to a message—e.g., you typically don’t want a newly

deployed saga to start reacting to messages that are from a year ago.

All these methods return raw SQL that is injected3 directly into the query that checks if some saga is ready to

continue. Scoop provides reasonable implementations for all of these methods, and you’re encouraged to build

your own. It’s called EventLoopStrategy because an event loop is the technical term for a thing that “periodically

checks if there’s something to do, and does it.”

Discoverability of handler topologies #

Since it so fundamentally influences the system you end up building, I want to spend a little time discussing the

original question that motivated EventLoopStrategy: how do we determine which handlers we should be waiting for? This

question stands at the center of how you implement resumeHappyPath (and resumeRollbackPath).

A good question to start with is if the handler topology of your system is fundamentally discoverable or not. What I mean by that fancy word cocktail is a system where you can, at any time, determine which components are participating, what topics they’re listening to, and what messages they emit. Perhaps you have a static registry in a JSON file that’s updated with each deployment, and part of each deployed service. Perhaps you have a component dedicated to providing that information, e.g., some sort of service registry. Perhaps it’s something else. But somehow, it is always possible to determine the correct answer to that question.

The reason this question is important is that it determines what options you have from the perspective of the CAP theorem—if your system is not discoverable, you cannot ever guarantee consistency, and all you can focus on is availability. Structured cooperation is fundamentally about enforcing consistency, so if you want to use it for that purpose, you need to invest the effort necessary to make your topology discoverable.

At least in theory, I can imagine there could be situations where it really might not be possible, by design. In those instances, you can still do a kind of “best-effort” structured cooperation—for example, you can guarantee that any service that ACKs a new message within X amount of time will be included in structured cooperation. It’s kind of like a train schedule—you need to be on board by a certain time, and once you’re on board, you all move as one piece. But if you miss the train, you get left behind.

My personal hunch is that the vast majority of practical systems are discoverable, at least in theory, so I want to spend some time discussing them. Even under the assumption of discoverability, things are not exactly trivial when combined with the reality of any distributed system of any complexity—things keep changing all the time.

Building and maintaining a handler topology #

In order to build a handler topology for the system, each service needs to publish this information about itself in some manner. Ideally, that would be done in some automated fashion directly from the code—there are a thousand ways to do that in any mature ecosystem. If you’re dealing with some horrible legacy system, maybe you can ask your MQ, or use something more advanced. Or maybe you like to watch the world burn, and require filling out a form with that information as part of the deployment process. But somehow, you need to do this.

Then, you need to make this data accessible to all other services. Collecting that data for all services and bundling it with each app would be nice, but not very practical, as you would need to deploy a new version of every service whenever it changed for any of them. A much more realistic approach would be to publish this information to some central place—could be in a database that’s accessible to all services, or your own custom service, or maybe something like Backstage. Just keep in mind that whatever this place is, it is a SPOF, and needs to be placed into the same QoS category as your MQ—if it goes down, the world goes down, or at least gets severely degraded.

That’s the easy part.

The difficult part is dealing with deployments that change this handler topology. There are two issues here:

- How to let the individual services know that something has changed?

- How to deal with running cooperation hierarchies that will be affected by what’s being deployed?

The former is basically cache invalidation. Each time the event loop of each service checks if there’s a saga that can be resumed, it needs to access the information of what other sagas it should be waiting for. Obviously, that can’t be a network request, because a) that would take forever, and b) it would probably hammer your registry into oblivion. So each service needs to cache a copy and be notified when it’s no longer up-to-date. This needs to be part of the deployment pipeline. 4

The latter involves determining which services will be affected by the change (e.g., those that have a handler that publishes messages whose handlers are affected by the deployed change—either their behavior is being changed, or a new handler added, or an old one removed, etc.), and doing two things:

- Notifying them to pause processing of new messages (and unpausing them after the deployment is finished)

- Waiting for them to finish processing any existing messages (or, alternatively, cancelling any that are currently running)

If you don’t do that, you could get into any one of many inconsistent states—some handlers are running old code, some are running new, some know they should be waiting for a new handler at a certain step, some don’t and some handlers start processing a message from the middle of a series of steps but didn’t process messages emitted in previous steps, and so on.

Obviously, this isn’t trivial and involves consideration of lots of edge cases, e.g., how long it’s acceptable for a given message to not be processed, or how long it’s acceptable to wait for handlers to finish doing their thing. You also need to properly handle any failures, e.g., if a handler was paused and then the deployment fails down the line, you need to unpause it again5. As hinted at in the previous two footnotes, all this corresponds exactly with what a saga is, publishing messages to topics is a very natural way to solve this problem, and the challenges involved are precisely what structured cooperation was designed to solve.

I don’t presume to tell you how you should or shouldn’t solve any of this, mainly because the landscape is so heterogeneous that I don’t really believe there is any way of formulating a sensible answer. But whatever the answer might be in your particular case, you have the option of using structured cooperation itself to help you implement it.

One final note on EventLoopStrategy—Scoop contains a dummy implementation that only works if all services are

actually instances of the same service (i.e. same .jar). Each time a saga starts listening on some topic, it’s added to a local registry

(basically a HashMap) that is then used for reference when building the list of handlers to wait for. Naturally this

isn’t an implementation that’s viable for production use, although it’s still powerful enough to allow you to scale a

given app horizontally with no additional work. Its main purpose is, as with Scoop itself, to convey an idea.

Rollbacks #

We’ve mentioned rollbacks quite a few times, but we’ve been putting off taking a closer look at their semantics. Let’s fix that.

First, to recap:

- Each saga step also defines an associated compensating action, which reverses whatever effect the step itself had. The default value is a lambda that does nothing.

- When an unhandled exception is thrown during the execution of some step, the compensating actions are executed in the

reverse order.

- As a consequence, if any messages were emitted during the execution of a step, and any sagas reacted to those messages, the compensating actions of those sagas are run first (again, in reverse order), and only then is the compensating action of the “parent” step run.

As we did when explaining the rudiments of how Scoop works a few paragraphs ago, it’ll be better if I first show you a

few examples of what the message events look like in various rollback scenarios, so here are a few sagas (omitting the

EventLoopStrategy) with their associated message events when they are triggered. As before, I’m truncating any UUIDs

to the last 4 characters, and excluding some columns (id, created_at, coroutine_identifier and

cooperation_lineage). Unlike before, I’m no longer excluding the exception column, but I’m obviously not including

the full serialized JSON, instead opting for a symbolic placeholder.

// a handler failing in a step never actually publishes any

// message emitted from that stepp, since the transaction

// doesn't commit

saga("root-handler") {

step { scope, message ->

scope.launch("child-topic", JsonObject())

throw RuntimeException("Geronimo!")

}

}

| message_id | type | coroutine_name | step | exception |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8aaa | EMITTED | null | null | null |

| 8aaa | SEEN | root-handler | null | null |

| 8aaa | ROLLING_BACK | root-handler | 0 | RuntimeException(“Geronimo!”) |

| 8aaa | ROLLED_BACK | root-handler | Rollback of 0 | null |

saga("root-handler") {

step(

invoke = { scope, message -> },

rollback = { scope, message, throwable -> throw IllegalArgumentException("Geronimo again!") },

)

step { scope, message ->

scope.launch("child-topic", JsonObject())

throw RuntimeException("Geronimo!")

}

}

| message_id | type | coroutine_name | step | exception |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a8bf | EMITTED | null | null | null |

| a8bf | SEEN | root-handler | null | null |

| a8bf | SUSPENDED | root-handler | 0 | null |

| a8bf | ROLLING_BACK | root-handler | 1 | RuntimeException(“Geronimo!”) |

| a8bf | SUSPENDED | root-handler | Rollback of 0 (rolling back child scopes) | null |

| a8bf | ROLLBACK_FAILED | root-handler | Rollback of 0 | IllegalArgumentException(“Geronimo again!”) |

saga("root-handler") {

step { scope, message ->

scope.launch("child-topic", JsonObject())

}

}

saga("child-handler") {

step { scope, message -> }

step { scope, message ->

throw RuntimeException("Geronimo!")

}

}

| message_id | type | coroutine_name | step | exception |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5e96 | EMITTED | null | null | null |

| 5e96 | SEEN | root-handler | null | null |

| c714 | EMITTED | root-handler | 0 | null |

| 5e96 | SUSPENDED | root-handler | 0 | null |

| c714 | SEEN | child-handler | null | null |

| c714 | SUSPENDED | child-handler | 0 | null |

| c714 | ROLLING_BACK | child-handler | 1 | RuntimeException(“Geronimo!”) |

| c714 | SUSPENDED | child-handler | Rollback of 0 (rolling back child scopes) | null |

| c714 | SUSPENDED | child-handler | Rollback of 0 | null |

| c714 | ROLLED_BACK | child-handler | Rollback of 0 | null |

| 5e96 | ROLLING_BACK | root-handler | 0 | ChildRolledBackException( RuntimeException(“Geronimo!”) ) |

| c714 | ROLLBACK_EMITTED | root-handler | Rollback of 0 (rolling back child scopes) | ParentSaidSoException( ChildRolledBackException( RuntimeException(“Geronimo!”) ) ) |

| 5e96 | SUSPENDED | root-handler | Rollback of 0 (rolling back child scopes) | null |

| 5e96 | SUSPENDED | root-handler | Rollback of 0 | null |

| 5e96 | ROLLED_BACK | root-handler | Rollback of 0 | null |

The “scopes” in “rolling back child scopes” is referring to the CooperationScope we briefly mentioned above.

Basically, it is a synonym for what could intuitively be called “message hierarchies,” i.e., “rolling back child message

hierarchies.”

I’d like to give more examples, but you can see that the table starts getting pretty long, so I’ll refer you to the

test

suite

instead—I think playing around with different scenarios and looking at what the message_event table looks like

after is the easiest way to understand it.

Here are the most important points:

- If an unhandled exception is thrown in some step, instead of writing a

SUSPENDED(if it’s not the final step) orCOMMITED(if it was the final step) message event, aROLLING_BACKis writen. AROLLING_BACKis, in a sense, semantically similar to aSEEN, in that it signifies a “start” of something—whileSEENis the start of the happy path, aROLLING_BACKis the start of the rollback path - When that saga is next picked up for execution, the last finished (= the local transaction committed) step is

looked up, and the set of messages emitted in that step is built from the

EMITTEDrecords corresponding to the step. AROLLBACK_EMITTEDis written for each such message, after which the saga suspends (aSUSPENDEDis written), and is not picked up again until all child sagas have finished rolling back (as determined by theEventLoopStrategy). Only then is the compensating action of the step actually run, after which anotherSUSPENDEDis written, and the process continues for previous steps. - Child sagas react to the

ROLLBACK_EMITTEDby writing their ownROLLING_BACK, starting the same process for themselves. - If all steps rolled back successfully, a

ROLLED_BACKis emitted—the equivalent ofCOMMITTEDfor rollbacks. - If an unhandled exception is thrown during the execution of any compensating action, a

ROLLBACK_FAILEDis emitted, and the compensation is halted there. - If multiple failures happen in different children, the exceptions are combined (i.e., no failure is thrown away).

All this is really verbose to write out, but the principles are actually fairly simple. The basic rule to remember is that rollbacks amount to “running the sagas backwards”—pretty much all aspects of the implementation follow from that.

There is one last thing I should mention before moving on—each step() actually accepts a third parameter, also a

lambda, called handleChildErrors. Any unhandled exceptions that bubble up from children are first sent into this

function. If it returns normally (i.e., doesn’t throw an exception), the exception is considered handled, and execution

goes on as if the child completed normally. This is basically the semantic equivalent of a catch block wrapped around

all child executions from that step, and allows you to do things like retries (you can emit messages from there in the

same way), or ignoring child failures.

However, you should know that this is one of the things whose actual implementation is a little half-baked, and there

are various things you need to be aware of when using it. All of them are solvable; I just didn’t invest the time to do

so. The main thing you need to take away is that having something like handlerChildErrors is important for the ability

to implement certain features.

The default implementation always throws whatever exception is passed into it.

CooperationFailure & CooperationException #

Since structured cooperation is, by design, language agnostic, you can have services running code in completely different languages all participating in a message hierarchy. If a failure happens in one place, it needs to be representable in whatever it bubbles up to, i.e., if a handler in Python emits a message that is picked up by a handler in Haskell, and that handler fails somehow, we need a way to represent that failure in the Python handler as well.

Therefore, a common protocol for representing failures is a necessary part of structured cooperation. Scoop provides an

implementation via CooperationFailure, which is a data structure containing data typically associated with a

failure—the type of failure, a message, a stack trace, and a list of causes. This is what determines the serialized

data in the exception column. Inside Scoop, a JVM implementation of structured cooperation, this is then translated to

a CooperationException, which is what is then thrown around. The concept of CooperationFailure pertains to

structured cooperation as a whole, and its format must be agreed and adhered to by all participants (same as, e.g., that

there is a message_event table, what is written to it, and when). The concept of CooperationException is specific to

Scoop, which is one of many possible structured cooperation implementations, in one of many possible languages.

You should also note that even though there is a standard representation of a failure across systems, you should be very wary to actually using that representation as part of any sort of code logic (e.g., checking for a specific type of exception bubbling up from children), because if you do that, you’re tightly coupling your handler to code in a service that’s far away, and the format of the failure must be treated as part of the public API of that specific service—just, e.g., refactoring the name of an exception could break your code.

While structured cooperation fundamentally does introduce coupling, it only introduces causal coupling, not procedural/behavioral coupling. If procedural coupling is what you need, then you probably should be using some form of RPC, not “fire-and-forget” messages.6

Cancellation requests #

Canceling a running saga on request is actually really simple to implement. A special kind of message event type,

CANCELLATION_REQUESTED, is written, and the default EventLoopStrategy used by Scoop checks for it in its

giveUpOnHappyPath and giveUpOnRollbackPath implementations. That’s pretty much all it takes.

Undo/rollback requests #

Due to the way it’s designed, Scoop supports doing rollbacks whenever you want—even if a saga is already completed,

you can just write a ROLLBACK_EMITTED and all the magic just works. So you get undo for free.

The only thing you should be wary about is rolling back anything but a top-level message hierarchy. While there’s nothing technical from stopping you from rolling back a subhierarchy, you’re essentially transitioning the system into an inconsistent state, which should be done with caution. But Scoop allows you to do both.

CooperationContext #

The last fundamental building block incorporated by Scoop which we’ve been glossing over until now, is

CooperationContext, which is a way to share data across the entire message hierarchy. Basically, it’s a writable

object that’s accessible in all steps in all sagas that participate in a given message hierarchy, and it’s crucial for

implementing certain features, such as the try-finally used for resources or deadlines (discussed below). As we

mentioned in the last article, you can think of it as the equivalent of reactive

context,

CoroutineContext, etc., if you’re

familiar with those concepts. If not, don’t worry about it.

Here’s an example:

data object MyContextKey :

CooperationContext.MappedKey<MyContextValue>()

data class MyContextValue(val value: Int) :

CooperationContext.MappedElement(MyContextKey)

saga("root-handler") {

step { scope, message ->

scope.context += MyContextValue(3)

scope.launch("child-topic", JsonObject())

}

step { scope, message ->

// logs 3

log.info(scope.context[MyContextKey]!!.value)

}

}

saga("child-handler") {

step { scope, message ->

// logs 3

log.info(scope.context[MyContextKey]!!.value)

}

}

The implementation is heavily inspired by Kotlin’s

CoroutineContext, although you

don’t need to know anything about that to understand it. All you need to know is that a CooperationContext can be

thought of as a HashMap, associating keys (instances of CooperationContext.MappedKey) to values/elements (instances of

CooperationContext.MappedElement, which is propagated across the message hierarchy in a particular way. The rules of

this propagation is the main thing that you need to understand.

The launch method on messageQueue, which is used to launch top-level messages from outside of a saga, allows you to

add a context parameter—this becomes the context in the first step of all sagas that react to that message. A saga may

mutate its own context at any point, in which case this mutation will be seen in all subsequent steps. Additionally, all

launch methods on scope inside a step also allow you to pass a context value, which is then combined to form the

context of the first step of any child handlers that react to that message. Any changes done inside child handlers

only propagate to their children, i.e., CooperationContext allows you to send data from parent to child, but not the

other way around.

saga("root-handler") {

step { scope, message ->

scope.context += MyContextValue(1)

// logs MyContextValue(1)

log.info(scope.context[MyContextKey])

scope.launch("child-topic", JsonObject(), ChildContextValue(2))

scope.context += MyContextValue(3)

// logs MyContextValue(3)

log.info(scope.context[MyContextKey])

// logs null

log.info(scope.context[ChildContextKey])

}

step { scope, message ->

// logs MyContextValue(3)

log.info(scope.context[MyContextKey])

// logs null

log.info(scope.context[ChildContextKey])

}

}

saga("child-handler") {

step { scope, message ->

// logs MyContextValue(1)

log.info(scope.context[MyContextKey])

scope.context += MyContextValue(10)

// logs MyContextValue(10)

log.info(scope.context[MyContextKey])

// logs ChildContextValue(2)

log.info(scope.context[ChildContextKey])

}

}

Things get a little more interesting when rollbacks are involved. The context traverses back up the steps in reverse, same as the execution flow. If, in a step, child rollbacks are triggered, the context travels to them as well, where it is combined with the context from the child’s last step (the “parent” context takes precedence if both contexts have any common keys).

CooperationContext is the building block upon which deadlines and sleep() are built—the final features we’ll talk

about here. Since this post is already alarmingly long, I’ll restrict myself to a few paragraphs and invite you to take

a look at the test

suite to

see them in action.

Deadlines #

The concept of deadlines is how Scoop implements timeouts, inspired (as is Scoop itself) by the work of the wonderful Nathaniel J. Smith. I recommend you read his insightful thoughts on timeouts and cancelations.

A deadline is a time by which a message hierarchy must be completed. Scoop allows you to specify a deadline for the happy

path, a deadline for the rollback path, and a deadline for both paths combined. All three deadlines are represented as

their own CooperationContext keys, which are respected by the default EventLoopStrategy implementations giveUpOnX

methods. The way CooperationContext propagates across the hierarchy ensures that a deadline applied to a message

applies to all child messages as well, while also allowing parents to set stricter deadlines for their children.

Deadlines also implement a tracing mechanism that allows you to determine where the given deadline originated from.

Delayed execution, scheduling & periodic execution #

Delayed execution, a.k.a. sleeping, is implemented using two things:

- A

CooperationContextkey containing the time until which we should be sleeping - A dedicated handler, built into Scoop and listening to a dedicated topic, that uses a custom

EventLoopStrategywhich only runs the handler after the time elapses.

Sleeping is then achieved by emitting a message on that sleep topic, with the appropriate context value.

This automatically gives you scheduling—things like “send a survey 2 days after a purchase” involve creating a saga

listening to the purchases topic that sleeps for 2 days as its first step. It also gives you periodic execution—a

saga which first sleeps for the period of execution, then emits a message to the same topic to which it listens using

scope.launchOnGlobalScope, then proceeds with whatever it is supposed to do.

Next steps #

There’s more we could talk about. For example, we could talk about how the contents of message-event impact

observability & tracing, and how they are invaluable debugging tools—so much so that when I implemented a stripped

down version of structured cooperation in an Axon app I was

maintaining, it immediately became the first place anyone would go when there was any kind of problem. It also allowed

us to catch a really, really nasty

bug— I shudder to

think what debugging that would look like without it.

But I’ll leave it at that and talk about one final thing—where we go from here.

Obviously, the first thing that needs to happen is that the community needs to pound at everything I’m talking about here. I expect there to be at least some pushback, because, like in both preceding applications of the idea (more on this in the next article), structured cooperation will probably make certain patterns obsolete, and people who are used to applying and thinking in terms of those patterns aren’t going to like having to learn to do things a different way.

To that end, I’d like to ask any readers with thoughts on the subject to please create an issue. Anything from “How would one do X using structured cooperation?” and “Wouldn’t X be a better approach to solve Y?” to “I see problem X in the way things are implemented” and “We should implement this in X next,” and any other thoughts you might have, are welcomed. Please do your best to read through existing issues and see if there isn’t one that matches what you want to say first, and I’ll do my best to answer them all as quickly as I can.

Assuming the community decides that there is value in this approach, the next step should be to put it to practical use.

As I’ve mentioned throughout both articles, structured cooperation is a concept, and it is implementable in any

language, in any framework, and on top of any infrastructure. Unfortunately, that also makes it a little difficult to

disseminate as a batteries-included package, because the landscape to which it is applicable is quite diverse. Scoop is

built in Kotlin on Postgres, but you’re probably not using Postgres for messaging. Perhaps you want to implement the

equivalent of message-event on top of whatever MQ you’re using. Perhaps you want to keep using a (shared) database for

that, but perhaps it’s not Postgres. Perhaps you want to move Scoops event loop to a different place, e.g., run it in a

dedicated service, or perhaps you’re feeling adventurous and want to implement it directly inside

Postgres. Perhaps you have a completely different idea of how structured

cooperation should be implemented. And perhaps you might want to do all that in 20 different frameworks and 20 different

languages.

That’s one reason that I’m not currently pursuing turning Scoop into a production library—this will clearly require a

community effort, and solving it for a single combination of (structured cooperation implementation, infrastructure, framework, library) wouldn’t make that big of a dent. Rather, I think Scoop has value as something like a reference

implementation—something others can consult when implementing structured cooperation in their environment of choice.

That being said, if there’s serious interest from the community and people willing to participate and/or sponsor the work, I would consider working on polishing the JVM version and getting it to a production-ready state. At the same time, I should stress that I’m just one guy, with a normal 9-5 job, so my capacity is fairly limited. In any case, feel free to let me know in the corresponding issue.

Where to go from here #

If you’ve managed to keep reading until here, thank you—there’s a lot to unpack here, and it can be a little overwhelming.

If you want to learn more about how Scoop is implemented or play around with it, head on over to the GitHub repository. Otherwise, feel free to continue to the final article of the series. I should note that this one is not necessary for understanding structured cooperation. It will, however, help convince you that the effectiveness of structured cooperation isn’t something that just happens randomly, but that there’s a deep reason involved. In this last article, I’ll show you that it is actually just the latest incarnation of a concept with a very rich history that has had a tremendous impact on the entire programming industry over the course of the last six decades. See you there.

-

And since this is UUIDs we’re talking about, we can safely change this to “

cooperation_lineagecontains<some UUIDs>,” orWHERE cooperation_lineage @> <some UUIDs>in Postgres. This kind of querying is used extensively in Scoop, and Postgres allows you to build an index for it. ↩︎ -

If you’re getting dizzy imagining the mounds of data this approach generates, don’t—you have lots of different options. Scoop only needs this data while the saga is running—after that, you only need to retain it if you want to support user-requested rollbacks (and even then, things could be reimplemented so you’d only really need the values of the cooperation context). Therefore, from that point on, you can just treat the contents of

message_eventas logs—define a retention period based on how long you want to be able to debug comfortably, after which you either remove the data, move it to cold storage, or whatever. Heck, you could just nuke it right after a saga finishes running. You could have different policies for different sagas. The sky is the limit here. ↩︎ -

This is bound to make people green in the face, but again—I’m trying to communicate an idea here. Focus on that, and be a loose lily floating down an amber river. ↩︎

-

A nice way to do that would be to have a

deploymenttopic that all services could listen to, where any topology changes would be published as part of the deployment pipeline. Of course, we’d also like to wait for all services to acknowledge they’ve updated their cache, so we don’t get into a situation where we deploy a new handler, and there’s a time window where some services know that they should wait for it, and some don’t—that could lead to messy situations. In other words, we’d like to publish the message and wait for all services to finish updating their cache. Do you see where I’m going with this? ↩︎ -

Notice how we want to unpause a handler regardless of how the deployment ends. Handler inactivity is an expensive thing—a resource. ↩︎

-

I should note that messaging is absolutely a way to implement RPC, e.g. you send a message (typically called a command) to a topic, and receive a response on another. ↩︎